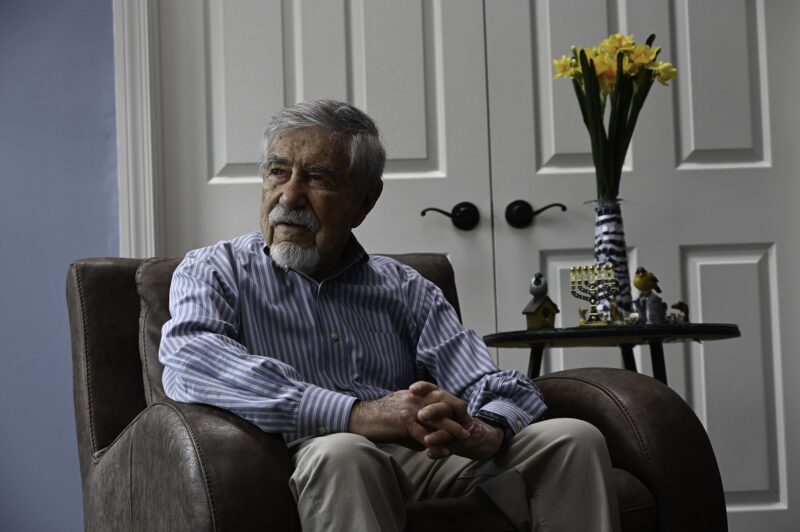

Ben Walker

Holocaust Survivor

“I was born in 1935 in Romania, in a small village called Nepolocauti, which was then part of northern Romania. I grew up in a rural area that was both beautiful and peaceful, and I can say without a doubt that it was one of the happiest periods of my life. Unfortunately, that time came to an abrupt end in 1941, when Romania formed an alliance with Germany – a pact that turned our lives into a living hell.

I still remember the knock on our door. Romanian police officers entered our home and ordered my parents, Aharon and Sali, my younger sister Katie, and me to leave our house and report to the nearest train station within three hours. When we arrived at the station, we were herded like livestock onto an overcrowded cattle car packed with people. We had no idea where we were being sent – or if we would survive the horrific journey. Fortunately, the journey lasted only ten hours, though it felt like an eternity. At its end, we arrived at the Dniester River, where we were taken off the train and ferried across on a barge to the city of Mogilev, to an area I can only describe as a Jewish ghetto.

After several months in Mogilev, we were forced to march in a death march to a farm near the city of Kopigorod. We walked through the cold and snow toward what was, in reality, a makeshift concentration camp. Those who couldn’t keep pace were simply shot – left to die where they fell, their bodies abandoned in the snow. We were forced to remain on that farm, which I can only describe as a concentration camp, for three and a half years.

We endured severe hunger, disease, and constant humiliation. Tragically, my father and baby sister did not survive that horrific period. They died in that very camp. Life, if it can even be described as such under such inhumane conditions, drives people to the edge. They will do whatever it takes to survive.

One of the images I cannot forget to this day is that of a young boy – I believe he was around ten years old, whose parents had just died. The boy took a stone and tried to use it to remove his parents’ gold teeth, hoping he could trade them for bread. He managed to survive for a few more days, and then he, too, was gone.

To increase your chances of survival during the Holocaust, you had to be seen as valuable. My mother, along with other women in the camp who knew how to knit, managed to use their skills to knit wool clothing for the Romanian soldiers who guarded the camp. Through her knitting, she was able to obtain slightly better living conditions and extra food for us, something that significantly improved our chances of survival. Despite this modest improvement, my mother constantly feared that she would die and leave me alone. I don’t know how she managed it, but somehow she found a way to get me into an orphanage, where I remained until the end of the war.

When the war finally ended, my mother and I were reunited. A few years later, with the establishment of the State of Israel, we decided to immigrate to the world’s only Jewish state. During my years in Israel, I truly felt, for the first time, what it meant to be a free person. As I grew older, I enlisted in the Israeli army, and for the first time in my life, I felt that I could protect myself and my people.

After living a few years in Israel, my mother married my uncle, who was living in the United States, and immigrated there to join him. In 1956, I joined my mother in the U.S., where I have lived ever since.

My experiences during the Holocaust were always like a ‘black box’ to me – I never spoke about them with my family.

I didn’t want to take on the role of the victim. More than anything, I wanted to distance myself from that nightmare and not allow it a place in my new life. I saw no reason to reopen those old and painful wounds. I realized that pure evil still exists in the world, and that we must stand against it. We must confront evil in all its forms, and it is crucial that younger generations understand what happened in the past, so that history does not repeat itself.

What surprised me about the 9/11 attacks was the fact that during the Holocaust, no Nazi was willing to sacrifice their own life to kill Jews – unlike those terrorists who were prepared to die to kill people of different backgrounds and beliefs.

A few years ago, I gave a talk about my life to teenagers at a synagogue in Atlanta, and one girl asked me a question that left me speechless:

“If you had the chance not to be born Jewish, would you take that?”

The question caught me off guard. My initial response was, ‘I don’t know.’

But what I do know is that we cannot choose our parents or the family we are born into. I also know that I am proud to be Jewish, despite all the suffering my people and I have endured. We are a people of survivors, and I am truly proud of that.”